DAVID AXELROD

by Egon

The other day, I called David Axelrod to clarify some points for this interview. I asked about fellow arranger extraordinaire H. B. Barnum. From there, Axelrod proceeded to weave an incredible tale. The day that he met Barnum, way back in the early 1950s, the two up-and-comers were hanging out with some female companions in Leimart Park in the western part of Los Angeles. A group of Chicano thugs, out to draw the blood of some unlucky sap at the Harvard Recreation Center, in a completely different part of the city, rolled onto the scene and mistook Axelrod for their boy. Before he knew what hit him, one of them had drawn a knife and sliced into Axelrod’s belly. As Axelrod clutched his stomach, cinching what would become a scar he carries to this day, Barnum took his wounded friend upon his shoulders and proceeded to—get this—knock down every last attacker that stepped forward as he made his way from thepark. Finally the cholos got the point and departed. “H.B. can seriously punch. He hits harder than Fernando Vargas!” Axelrod exclaimed. “If he hit you right now, with that left hook, you’re going down. He’s short, but he’s so powerful.”

David Axelrod’s life is sensational. Forget for a minute that the man produced some of the finest R&B and jazz albums of the 1960s for luminaries such as Lou Rawls and Cannonball Adderley. Forget Axelrod the visionary who, long before Shadow and his sampling contemporaries “endtroduced” themselves to the musical world, created the blueprint for classical melodies melded with the funkiest of backbeats. This interview would be worth reading for the intense anecdotes that characterize David Axelrod’s life.

But the name of the game is music, isn’t it? And as we all know, Axelrod is responsible for some of the most dynamic American music ever recorded. From David McCallum’s “The Edge,” to Adderley’s seminal “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” to his divine 1968 debut Song of Innocence, and the prolific beauty that followed —his creativity has never waned. He has yet to compromise his artistic integrity or release a wack album.

So take a deep breath and delve into our attempt to present the entire scope of David Axelrod’s musical life. From his birth in South Central Los Angeles, from his humble beginnings as jazzer Gerald Wiggin’s assistant, through lucrative days spent producing Capitol Records’s finest, to the calmer North Hollywood lifestyle he enjoys today, you’ll share our amazement with the blessed path David Axelrod walks.

Now Mr. Axelrod…

Make it Dave, or Axe—that’s what all the guys call me…

Yeah, I see it on the back of all the album covers. For real, I can call you “Axe”?

Of course! Sure…

The privilege! Okay, “Axe…” You were born in South Central Los Angeles.

1933. I grew up there. Knew it like the back of my hand and still do.

Your longtime friend and musical compatriot Don Randi said you grew up in the Black part of town…

It was Black…

But you’re not Black…

No, but I was raised by Blacks. For a while I thought I was Black.

But this wasn’t any kind of identity crisis, was it? You were just associating with the folks that surrounded you.

Exactly. But it got pretty bad. Gerald Wiggins had to straighten me out a few times. See, I had reached the point where I was asking questions. For instance, if someone was talking with Gerald about a record, I’d butt in and ask, “Well, is he colored?”—which was the term at the time—”Or is he grey?” And we’d get into it! Wig would say, “Stop asking that question! What you should be asking is, ‘Is he good or isn’t he good?!’ ” I had reached a point where I honestly thought, “If he’s a White musician, he can’t play.”

Seriously?

Well, I was also very young. See, I never make a big deal about where I grew up. To my father, the idea of bigotry was totally brainless. But the fact that we had no money meant that we kept moving east during the White Flight. So all the Whites are moving west—’cause they’re running from the Blacks—but we’re moving east ’cause we had two boys, two girls, my father and my mother! He needed a place with three bedrooms—wherever that was, we landed.

So except for music, was race ever an issue for you?

Never! It shouldn’t be an issue! That’s the problem today. The biggest issue we face—the biggest—is race!

Let’s focus on the music though. White music in the ’30s is much different than Black music of the ’30s.

Very true. But you have to understand something. If you’re going to follow the tradition of jazz, you have to know everything. Today, I talk to all musicians—White, Black—it doesn’t make a difference. But most don’t even know who Ben Webster is, and that’s a tragedy! You should know the tradition of where you’re coming from—regardless of the color of your skin.

Understood.

I was very lucky, ’cause I had an older brother who wanted to become a musician—a drummer. So he constantly practiced to all of these big-band records. I would sit with him and wind up his record player—for that he’d pay me a nickel! [laughs] I’d become exhausted, but he didn’t care. I guess he was twelve or thirteen years older than I was. So if I was five, he was seventeen or eighteen. And I don’t think he cared how tired I was getting! But I got to hear the music. He listened to a lot to Benny Goodman and Count Basie. Those were his two favorite big bands.

At the tender age of five, you’re absorbing jazz. But as you grew older, you weren’t just playing your brothers records; you were picking your own. What did you gravitate towards?

In my early teens, it was mainly rhythm and blues. I loved rhythm and blues. By the way, people are insane if they think that rhythm and blues started with Vee Jay Records in Chicago. It started in Los Angeles with Amos Milburn. “Bewildered”—remember that one?

Of course.

Well, we all dug him, ’cause he dressed so sharp and he always had an inch and a half of Chesterfields sticking out of his pockets. It was so hip and we were young, like fifteen years old. It would be the equivalent today of someone having an inch and a half of reefer in his pocket.

This is around 1950. You’re surrounded by intense music.

Well, we rolled through all these clubs. Like the Million Dollar Theater. They would get all these R&B acts, and the big bands. They’d run a picture and then they had the live acts.

So you’re prowling the streets of Los Angeles, looking for music.

Always! See, my father died when I was twelve. And the War was on. My mother couldn’t control me and there were no guys around that could—they were all in the service! So more or less I did whatever I felt like doing. My friends and I loved to go to these clubs. And I think there were only a few of us that picked up on the music; most of the guys were going just to drink. It was corrupt back then. Cops didn’t care; they were getting paid off. You just had to be cool.

Any acts that you remember?

Of course! T Bone Walker! Like B. B. King said, “He’s the father of us all.” There are three great drunks in my life. In chronological order: 1] T Bone Walker 2] Johnny Mercer, and 3] an arranger named Gordon Jenkins. I call them “the greatest” ’cause I was so aware of all three of them. Just to sit with them and talk was so great… Where were we?

Who else were you listening to?

Right! Well, Amos, Roy Milton and his Solid Senders featuring Camille Howard, Pee Wee Crayton, Louie Jordan. I started getting into a lot of trouble in Los Angeles. So I moved over to the East Coast, ’cause I had lots of relatives out there. While I was living in New Jersey, I met this guy in Englewood. He owned a gas station and worked for my uncle, washing his delivery trucks—all one hundred of them! He had lived in L.A. and had graduated from Dorsey High School—where I had gone. How weird is that?

What was his name?

James Samuels. And he became my best friend. He started bringing me to the Black Elk Club.

The Black Elk?

I don’t know much about those clubs, but they were very well known. And segregated. There was a Black Elk club, and a White Elk club. At that time, I don’t care if it was New Jersey, it was no different than Biloxi, Mississippi. It was very segregated. Suddenly all these people adopted me. They were my closest friends.

Were you checking out jazz?

Finally! James took me into New York City. We went to 52nd Street. This was the first time that I had heard real jazz. Jesus! I couldn’t believe it!

Who were you checking out?

Everybody! Name it, they were there! It was like a documentary. The Three Deuces, the Onyx, and all those things. We even went one Friday night to the Savoy Ballroom. It was such a thrill—who hadn’t heard of the Savoy? When I went back to L.A., I was seriously listening to jazz. All bebop—that’s all I cared about.

When did you return to L.A.?

1953, I think. I’m bad on dates; I’m not a kid anymore. But I was about twenty years old. You have to remember—I was born and raised in L.A. I have blood as thin as water! So when that first winter hit in Jersey, man… I couldn’t deal with it! So I spilt and joined the Marine Corps. From there I moved back to L.A. And I fell into a heroin jones. One day I was on Central Avenue, the heart of the Southside. All the great clubs and places to eat—the Texas Barbecue—man, I loved it. Anyway, I was at the Turban Room and there was this group playing, the Gerald Wiggins Trio.

Did you know who he was at the time?

Nope, I had no idea. At that time, I thought Bud Powell was the best on piano. Anyway, I was waiting for a connection and I was ordering drinks. Finally, Slim, the bartender, looked at me and said, “Guess what kid? Time to straighten out the tab!” He’s looking at me, and I’m a young White kid on Central Avenue. Because of my jones, I probably weighed 125 pounds. [laughs] And he ain’t no fool. So I’m thinking, “If I pay this guy and my man shows up, I ain’t gonna score.” What am I going to do? Slim could read what I’m thinking. Bartenders, if they’ve been around long enough, know what’s happening. Especially on Central Avenue. But all of a sudden, this voice says, “Don’t worry about his tab.” And it was Gerald Wiggins. He said he’d take care of it. I thought that was some really strange stuff. Anyway, my guy never shows up—a great disappointment. [laughs] So Wig asked what I was doing. And I said, “Nothing really.” I didn’t have a car, and he asked where I lived. He said, “I’ll give you alift.”

So you’re kicking it with this great jazzer. Were you excited?

Well, to tell the truth, I thought he was a faggot. So I was thinking, “I’ll roll him, take him for his goddamn money.” So we went up to his place. He opened the door—and there was his wife!

A great deal of relief for you?

Well, I don’t think I felt relieved. It was probably good for him, ’cause I was seriously gonna bounce him and snatch whatever he had. [laughs] But it was like The Man Who Came to Dinner.

What’s that, a film?

Yeah! I keep forgetting how young you are! It’s about this big syndicated columnist, very powerful guy, who slips and falls on some guy’s walk and takes over the whole house. It was funnier than hell.

And that’s the way it became with you and Gerald.

Yeah! [laughs] I started hanging with him eighteen hours a day. We went everywhere. It was great. He introduced me to so many great guys…

And what were you doing?

Sitting around and listening to them talk jazz. You can learn a lot from listening. He introduced me to a lot of great guys that I made great music with later in life.

Like whom?

Bill Green, Buddy Colette, Johnny Kelso… A bass player named Don Bagley.

And he never explained why he picked you out of the crowd that night in the Turban Room.

Never! To this day. See, Gerald deals in whims anyway. [laughs] I ask him why and he stares at me like I’m an idiot.

Well, it’s good for us that he picked you. He broke you into creating music.

Yeah. It was weird the way it happened. I was with him for, like, four years. And he had never really explained anything about music. But because of these conversations with all of his friends—including the greatest instrumentalist ever, Art Tatum…

Really—Art Tatum, the pianist—the best ever?

Well, it can’t be a horn player, ’cause Art Tatum has ten fingers, which means ten instruments. And he was so incredible—they’ll never be another. I don’t care about Arthur Rubinstein. I’ve heard his records, and I have some of them. There’s no classical player that has chops like Art Tatum.

What a life you lead! And your big break?

It happened after I was already in the business. I was working for Southwest Distributing Company. A terrible, terrible job, but it helped me get into records, ’cause the owner, Bob Sherman, had a label—Tampa Records. He had me do promotions. And he made a record with a drummer named George Jenkins—The Last Call . I knew George ’cause he lived on 30th Street. I put that record on the charts. We went around the States, and I really hustled that record. Man, I was good at promotion. Anyway, one day I was with Wig, and he was shaving. All that time we’d been together, and I’d never sat down by the piano with him in the room. All those years! So I did something on the piano, and Gerald burst out of the bathroom. I’ll never forget this —he had his shirt off, and he had shaved one whole side of his face! I don’t know how you shave—

Not like that!

Yeah, I don’t either… But that’s the way he shaves. One whole side and then the other. Gerald is weird, man. Anyway, he told me to replay what I’d played. And I had no idea what I had done. He stared at me for a while, and then he said, “You’re a dummy.” And he turned around and went back to shaving. So I kept fooling around, and I played the pattern again. And this time I remembered what I’d done. So Wig finished shaving, put on his shirt and grabbed a sheet of manuscript paper. He wrote out the C scale, with the treble cleft and the bass cleft. Then he told me to go buy a musical notebook. He said, “Put notes all over it in the key of C, so whenever you see those notes you’ll know them.” Then we went to F major. One flat there… Then we went to the key of E flat major. Then he said, “I want you to get a book of scales and learn those notes by heart. Do it for every key and their relative minors.” And when I learned those lessons to his satisfaction, he said, “Now I’m going to teach you how to read music.”

So this is your “formal” training…

Oh yeah, very formal! [laughs] Well, he sat me down and played a metronome. He wrote out all the types of notes—eighth notes, quarter notes, whole notes—and then patted out the meter on his side. And that’s how I learned to read music!

So Wig taught you the basics. But you must have been practicing on your own.

All day long! By this time I’d landed a job at Motif Records. I met Jack Devaney. That man did so much for me! I have a feeling he’s dead now—last time I saw him he was a complete alcoholic, never sober. But this was 1956, and he’s an easy-going, nice guy. But he had clout. He was the West Coast Representative for Cash Box magazine. Down Beat was the jazz bible, but Cash Box was much bigger. People listened to him. Motif was owned by one of the wealthiest men in California—Milton W. Vetter—and Jack talked him into hiring me. Originally, I was a sales manager, but the guy who was producing was such a lunatic that he got fired. So next thing I know, I’m about to produce a record.

Were you confident in your ability? You were pretty young!

Yeah, I’ve always had confidence. I don’t know what it is.

So the first David Axelrod production—who and when?

Well, I used Gerald of course, ’cause I was comfortable with him. It was the Gerald Wiggins Trio. 1956. We did all these old tunes, “3 O’ Clock in the Morning,” etc… I don’t know the name of that album, but it’s the first one I did. And I knew my job. See, a producer is to music what a director is to film. What a director does, a producer should do. What is a song but a story anyway? The arrangement becomes the screenplay; the musicians and singers are the actors. The engineer is like the camera man. And the producer is the boss. You gotta pull it all together. That’s how I’ve always gone about it.

You produced Harold Land’s album, The Fox, around 1958 or ’59. That was a landmark record for you—we’ll answer “why” later. But what did you do between the Wig record and The Fox to build up your chops?

Well, remember that Motif was nothing more than a write-off. There really wasn’t that much to do. So I could do whatever I wanted, but four times a year I’d make a record just to keep it legal. Meanwhile, I was doing stuff for other labels. Devaney constantly got me gigs. I’d give him half, but there wasn’t much money. I’d get a hundred bucks or less for an album.

But you gained worthwhile experience…

Exactly! At the time, all the R&B labels were starting jazz divisions. Devaney spoke to the owner of Specialty and convinced him to hire me. Of course, the first record I cut was with Wig. We did Around the World in 80 Days. Specialty wanted another one, so I recorded Buddy Colette. They liked it. Then I did one with Frank Rossolino. See, in a Down Beat interview, I said that certain West Coast jazz was like “wet dream music.” That’s a great line, isn’t it? You knew something happened when you woke up but you got no satisfaction! Frank read that and burst out laughing. He called me up and said, “We have to record together!”

How did you two get along?

Just great. Frank was a terrific, funny guy. You know, many years later, Rossolino killed his wife and shot both of his sons. One lived, one died. Then he blew his brains out. Who would have believed that he had such a dark side? I don’t recall him ever being serious! Anyway, during the session, Frank mentioned to me that I should record Harold Land. A bit later, I got a call from Devaney. He set me up with an interview with the guy that owned Hi-Fi Records. Now that was a fairly good independent label. They hired me—for the most money I’d ever saw in my life, a hundred seventy five bucks a week. That was a lot of money for the ’50s. So I started doing some Arthur Lyman records. It was cool, I got my first gold record with him. But I got into jazz with Harold. You know, I took a big gamble with The Fox. I booked studio time at Radio Recorders under Hi-Fi’s name, and I personally borrowed the money to pay for it. Then I took the finished product to Richard Vaughn, the owner of Hi-Fi. Luckily he liked it and decided to buy it. So he asked me how much I wanted. I replied twelve hundred dollars. He promptly cut me a check that I then endorsed and gave to the dude I owed money to.

Did the record take off?

For a jazz album it did. But more importantly, since the Rossolino album never came out, The Fox was the hardest thing coming out of L.A. It was serious bebop. Incredible! Sounded like it was from the East Coast.

Indirectly, this record led to your introduction to Julian “Cannonball” Adderley.

And Cannon became the best friend I’ve ever had. The most intimate… There’s no adjective to describe how close we were. Lalo Schifrin called him “The Buddha of Music.” I wish I had come up with that line. Cannon was a wonderful man. When my son died, he called me from the University of Berkeley. He was on a sixteen-college tour. He was about to get paid a lot of money. But he cancelled the tour to stay with me.

During the worst period of your life…

Of course. Cannon helped me get through it. It was funny the way we met. 1962. I was working at Plaza Records and I was across the street in this room. In walks Ernie Andrews and Cannonball. They were waiting for Joe Zawinul to review some tunes that they were going to record. Well, Ernie sees me and walks over. And when he introduces me, Cannon goes, “Ah ha! The Fox! I knew our paths would cross some day!” It’s amazing, ’cause Cannon listened to absolutely everything. Now segue to Capitol Records in 1964. Six months after I get to Capitol, they sign Cannonball Adderley. He’s up in the executive office with the vice president, Voyle Gilmore, and the president, Allen W. Livingstone. They asked him which member of the production staff he wanted to work with. He said “Get me David.” See, there was a terrific jazz producer and arranger working for Capitol named David Cavanaugh. So Livingstone says to Voyle Gilmore, “Buzz Cavanaugh and have him come up here.” Cannonball says, “No, no, no!”—and he starts waving his hands, I can just picture it now—”I want David Axelrod.” Cannonball had heard The Fox, he knew that I knew what was going on with bebop. Cavanaugh was old. I loved Monk, but Cavanaugh thought that jazz had stopped with Basie.

So he was old fashioned.

Kinda, but he made some great records. He made a lot of hits.

But you get this new giant, Cannonball. What other stuff were you doing at Capitol at the time?

Mainly Lou Rawls.

Rhythm and blues…

Yeah, mostly R&B. But nothing was selling. You gotta understand something. Capitol was not geared to R&B. By the end of 1965, I had just about had it. And I had worked so hard to get there—to me, Capitol was it! See, I knew I made good records, but I couldn’t get them sold. So I had an idea—why not start a Black music division. I took this idea to Voyle. He thought about it, but concluded that Allen wouldn’t like the idea. So he took the proposal to the Executive Vice President of Promotions. And this guy liked rhythm and blues. See they had hired me to do R&B. I loved it, but I’m signing all these Black artists and no one is selling anything! There was absolutely no promotion. Just think about it. In 1965 when the Watts Rebellion happened, the White guys weren’t going to go down to the Southside to promote records. So I went down to Daisy Reynolds at Flash Records and hustled my own projects. And I knew if we had nothing but Black promotions people we could make it happen. And Allen[Livingstone] was so hip. He didn’t think that the majors would ever make it with R&B, but he said, “David, let’s give it a shot.” I love him to this day.

So Lou’s music starts selling better?

I’ll tell you something, the very next record we made was Lou Rawls Live—sold like a million and a half! Back then we only had gold, but it woulda gone platinum easily!

So you have gold records under your belt and the confidence of the president of Capitol. Were you producing Cannon at this time?

Sure. We had done a couple albums together that were really like “work.” But then we started to become good friends. It all began when we were recording an album in New York, where Cannon was living. On a break in the session, Cannon took me into the bathroom. He took out a glass vial, held his thumb in his palm, and made a fist around it. Then he poured some powder into the crack. And he told me, “I want you to do what I do.” I said, “Look man, I’ve been through that crap; I don’t need it in my life.” I thought it was heroin, but it was cocaine. I’d never even seen the stuff. This was astonishing, ’cause I’d taken everything known to mankind! [laughs] I made him laugh, and he blew the coke all over the place. He said, “I know your whole story, this is coke not heroin, for God’s sake!” He told me to be quiet and do what he was doing. I loved it immediately. It was a very different high than anything I’d ever done. We never abused it—I never did anything but sniff it. I’ll admit that between 1965and 1981, I spent a great deal of money on it. And I never wanted to quit it. It quit me! I had a very bad experience. One time, my pulse shot up to 266 beats per minute. According to my doctor I had a metabolic change. And, as you can tell, I’m very manic-y anyway.

Luckily you pulled through.

Well, it was very easy actually. We called my doctor and he said, “Give him 60 mg of Valium right now and have him chase it with a big glass of cognac.” The guy on the phone replied, “A big glass?! With his heart rate?” And the doctor said, “Shut up, and stop playing Florence fucking Nightingale. It’s to make the Valium work faster!” And it worked—I haven’t touched the stuff since.

Which is good…

No, it isn’t. [laughs] I liked it, and it never got in the way of anything. When I wrote music, it helped keep me awake—even Freud noted that. And I can rail off the names of musicians that are in their seventies that have been snorting coke for fifty years! And they’re still doing it! This was just a freak thing that happened to me!

Whew! Back to that session with Cannonball…

When we got done, he took Oliver Nelson and myself across the street to this funky bar. Cannon asked for cognac and the bartender looked at him like he was nuts. So Cannon asked for any kind of brandy. We all got these snifters and started drinking. Then he went to the phone booth and called his wife Olga—one of the most beautiful people I’ve met in my life—and he took us home for dinner. I thought this was great of Olga, ’cause now she had to make dinner for not only Cannon, but for Oliver and myself. When we got to his place, finished with dinner and were sitting around having drinks, he started bringing out all these records. All R&B. I know them all, but I started saying, “You don’t have the real stuff.” I started dropping all these names. He looked at me in disbelief. I knew everyone he was bringing out—Ernie K-Doe, Bobby “Blue” Bland…

But you’re saying, “You need to be up on these guys—Amos Milburn, Lowell Fulsom, and all that.”

Right! That really blew him away. He never expected it from me. That’s what made us tight.

This mutual appreciation for R&B makes its appearance in the jazz that you both created. For instance, Mercy, Mercy, Mercy—the second biggest-selling jazz record of all time.

That record caught everyone by surprise—and no one was more surprised than Cannon and me. We never went out to make a commercial record. But Joe Zawinul could write these terrific songs. He wrote “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.”

Very funky music. You hear the soul and R&B reverberate through every bar. That song gets its drive from the backbeat! You must have had something to do with this.

I always had input. We went through everything together, Cannon and I. If there was something I heard that wouldn’t be good on the album, I would say, “No go!”

And you’re a funky dude. You’re into this deep-dish R&B that the average person had no idea about. You were up on jazz, but you were definitely aware of the change in popular rhythm that R&B helped usher in. And on top of injecting funk into the jazz of Adderley, you’re doing the same with soulsters like Rawls and pop artists like David McCallum.

With McCallum, everything we did went top ten and gold. But I don’t think that people were buying the music. I think they were buying the little autographed pictures that we put in the albums. The little girlies were so in love with that guy! He was so cool, he just did his thing and people loved him. It’s a funny story how I got him to come to Capitol. I had read somewhere that he had broken Clark Gable’s record for the most fan mail received in one week. I thought, “Whoa! This little dude is doing something.” I had met him before when I had produced The Man From U.N.C.L.E. theme—David starred on that show. Now make no mistake—David came from a musical family. His father was a concert master and David had studied the oboe from the time he was a kid till he was fifteen or so. Anyway, at one of our weekly A&R meetings, I said I wanted to sign McCallum to Capitol. Voyle asked what I planned to do with him. I knew he couldn’t sing, and I didn’t want to have him recite spoken word over some lush arrangements, as was popular at the time. But I knew I’d do something! Voyle, who led the meetings, said, “That’s just not good enough.” He moved to the next order of business. But before we could do anything, Livingstone—who’d just been looking at Voyle and me—looked at me and said, quietly, “If you can sign David McCallum, do it.” That was it. Voyle got red in the face, but that was el jefe! The chief had spoken.

And he turns every record he’s on into gold. At the time you’re also doing quite well with Lou Rawls and Cannonball.

Are you kidding me? I’m golden boy! I’m the Oscar de la Hoya of Capitol Records! I could do anything I wanted to do. I was rich—making the equivalent of $700,000 a year!

This is around 1966-’67. David McCallum’s Music: A Bit More Of Me. There’s a song on that album, called “The Edge.” One of my favorite David Axelrod compositions.

I’m going to tell you something. Listen to that song close, especially to the chords. Everything I do, you’ll hear in that tune. I’ve done so much afterwards, but there is also something there—in the undercurrent—that is similar to that tune.

How’d you manage to sneak such a progressive song onto a pop record? For your arrangements, that funky rhythm—McCallum couldn’t have been responsible for that.

Well, we could give McCallum anything we wanted, ’cause we knew he was going to sell records. For the most part, we were making instrumental versions of hits. But I had to be careful—I had to say, “Will this song, which is in the top eighty of the Billboard top one hundred, make the top ten?” It was kind of a gamble, that worked out pretty well. On that record, McCallum wrote two tunes, H.B. wrote one, and I wrote one. And we all made out pretty well, ’cause those records really sold.

What is “The Edge” about?

Third-world countries. There are these areas of ramshackle houses that stretch for miles. People actually live in the containers used to ship Coca Cola bottles. It’s terrible. I saw it in San Juan. I thought that it couldn’t get much poorer than South Central, L.A. Well, guess what—dirt streets and these “Coca Cola shacks” for miles. That was “The Edge”—the edge of the world. Where else can you go? Well, you could kill yourself. But those people have so much spirit that they would never do that.

Such a powerful song. Starting with the guitars clashing with the brass, the whispering flute over that powerful backbeat. People now say that the song reminds them of the Wild West.

The Wild West? What the fuck does that song have to do with Wild Bill Hickcok? C’mon man, it’s about my people! I’d never seen poverty like that firsthand!

That was one of your few original compositions on your early Capitol productions. And a great indication of where you would travel to a few years later with your solo ventures. Did you ever explain to McCallum how you developed the concept?

No, he didn’t care.

You know, no matter how musical McCallum might have been, I always wondered what he really could have done in a session with you.

[laughs] David is a great guy. I always liked him. But the sessions were a little weird. There really wasn’t anything for him to do! This is what happened: When we were ready to record, he would get up and all these camera men would start taking pictures. That was it!

An image…

Of course! But is there anything wrong with that?

Whew! Halfway done, and we’ve barely even scratched the surface. Dynamic sessioners like Carol Kaye and Earl Palmer, the Electric Prunes, the breakthrough Song of Innocence, Songs of Experience, and the altogether mysterious Earth Rot, staff positions at Decca and Fantasy—and a new album based upon rhythm tracks that Axelrod cut to acetate in the late 1960s… Come back for our concluding interview—not to be missed!

After some time I finally called up David Axelrod for an interview. Some of you may know his early work, while others are hearing his beats sampled in Dr Dre or DJ Shadow albums, after being rediscovered by the hip-hop genre during years of obscurity. Traveling back as a jazz scout in the fifties, he's produced the likes of Lou Rawls, Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, the Electric Prunes, and is remembered for his two cool-whip Blake-orchestrations in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience in the late sixties. Composer, arranger, heavy-metal enthusiast, and L.A. native of Capitol Records, we talked about all these things at 10:30 in the morning at his North Hollywood apartment while preparing for an upcoming concert in London. Here's how it went down...

Carson Arnold: How are you doing?

David Axelrod: Terrible, I got the flu, but go ahead.

CA: The only albums I own of your's are Songs of Experience, Heavy Axe, the MoWax album and a few Electric Prunes things.

DA: You'll have to go to the store. You're in Vermont? Call Amazon.com, everything's been re-released. It's all on CD. Get Songs of Innocence, get Songs of Experience. Get two anthologies all from EMI.

CA: What are you working on now?

DA: I'm working on a concert on March 17th {2004} at Royal Festival Hall in London. It's pretty exciting. Both {old material and new stuff}.

CA: Things from The Requiem?

DA: I'd better...they'll kill me.

CA: Will there be new albums?

DA: Next year. There's gonna be an album out of this, of the concert. Two albums. I wouldn't mind, really, but it just seems those days are over. Companies don't like it.

CA: Your compositions?

DA: Well yeah, and then there will be some arrangements of some other people.

CA: Like who?

DA: Um...I'm gonna skip that. They don't know in London yet. {Asking about new material} Lately, I've been working on this concert for weeks. I have to do an hour and forty minutes worth of music. That's almost three CDs!

CA: Your track "The Little Children" reminded me a lot of Stravinsky's Cantatas.

DA: Igor? That's strange. I love Igor. I think, though, I was using more {Alban} Berg than I was Igor. Try and find a key in it. I mean, what key are we in?...I don't know either. Thing is, I've been going through tonal centers. Oh wait a minute, you're talking about the MoWax album?....Jesus. Listen, I just woke up and I'm sick as a dog, so bear with me, okay? Do you have ringing in your ears?

CA: More headaches, but it seems to be going away.

DA: You're lucky you're not in LA. I'm very serious, there's a virus here, because we're in the Pacific rim-- the gateway to the United States. And every virus that comes in from Asia hits LA so bad. I mean, I'm talking to you right now and getting all these chills-- I could have malaria. Of course my doctor, great buddy of many years, starts laughing. He goes, "How do you get malaria in LA, you idiot?" {Laughs} I don't know, but I have it. Where you gonna get malaria in North Hollywood?

CA: When I called you last time you had a flu, too.

DA: Whatever comes through here. There is no flu season in southern California, it's a year round situation.

CA: Do you play a lot of music so the neighbor's hear you?

DA: Well we have a work-room. We have a one-bedroom apartment, my wife and I, and downstairs I have a single apartment that I've turned into a work-room. I hate to call it a studio. Studio? What the fuck is that? It's a work-room, it's where I work. {Terri, my wife} is terrific. She's an angel.

CA: I was reading an article that Mojo did of you, where you said production wasn't an art. "I hate artists."

DA: That came up {Chuckling}...God. I never said that, it's not what I really meant, that it's not an art. I just don't like the term "art". I've never liked that term, I'm a musician. That's good enough for me. So many people are loved for being an "artiste". What the fuck is that?

CA: So what you, Phil Spector or Henry Mancini did wasn't art, it was just production?

DA: They're not artists either, don't you understand my point? They're workers, they work...I got so much shit for saying that it's unbelievable. Musicians that I know got very mad. "Why would you say something like that?" Of course it's art, for god sakes. I was just talking about the way certain people talk about "artistes" all the time.

CA: What do you think of sampling? You were you pretty much resurrected, maybe I don't wanna say that-

DA: That's a good term, though. Yeah, I feel like Lazarus myself, so why shouldn't you use it.

CA: Sure! So sampling-- you said "a machine can sound like the blues but it ain't the blues."

DA: That's right.

CA: So first of all, why would DJ Shadow or Dr Dre would choose you to represent their beats?

DA: Because I make good music, and they want good music. What they do with it, some people irritate me, but some people do it so well. I mean, I really wish I would've thought putting the intro behind where the orchestra first comes in the way Dre did on Next Episode. That was really hip.

CA: But what will happen in production when people can just sample one or two seconds? What's to hope to in producing?

DA: Well, I dunno, that would be subliminal. One second of music goes by so you don't really know if you're hearing it or feeling it. William Friedkin, the director, once admitted he throws in nine frames...Thirty-five millimeter film runs twenty-four frames a second. So what is nine frames? Are you really seeing it? {Laughs} If you say one minute that would be different. You wouldn't hear one second. You feel it.

CA: Somebody like Stan Brakhage.

DA: I don't know who that is.

CA: He took film and spliced it all up into different colors. Basically what John Cage did with music he did with film.

DA: I'm not hearing you well.

CA: (Must be my rotary phone. I'll speak louder.) With sampling, somebody like you who came up self-taught with classical music, now anybody can take a piece of music without knowing anything about music and sample just a beat.

DA: That's a bit of an irritant: The lack and knowledge of music in the entire industry. There are so few vice presidents of A & R today who know where middle C is, it's absurd. It's one of the things that's wrong with the industry. People just don't know music. And yet they're the hierarchy of their labels. How can you be the vice president of A & R and not know where the C chord is? That's crazy.

CA: Was it the same way back in 1968?

DA: No. When I was first interviewed at Capitol Records, the head of A & R was a man named Voyle Gilmore. There were so many musicians there it was unbelievable. Vole himself had been a drummer. As a matter of fact, he told me a story once that he use to go on the road with the Gum Sisters, which became Judy Garland, that was her original name. Poor Voyle, she use to call him. One day I went up to see him at his office and he looked like death eaten crackers, god he looked horrible. I said, "God, Voyle, you look terrible." He said, "I've been up all night. Judy called at about two-thirty and she kept me on until about five-thirty." And I just broke up laughing at that, because he had known her since she was a little kid. And whenever something was bad in her life, she'd call {him}. Point is, though, Voyle took out the score, the transposed score and he said, "Read me the chords, vertically." So I did. And he went, "Very good." Everybody on that floor knew music. Every producer was an arranger, and a good one.

CA: And now you're back in this new industry and still trying to produce good music within it.

DA: I'm going to. When I get to London, I check out of my hotel on the 18th, concert on the 17th, and I'm being picked up by a certain artist-- very big time artist-- and I'm going to stay at his place as a guest with he and his wife, and for two days we're gonna discuss his next album. He called me.

CA: And you can't say who that is?

DA: No.

CA: Not even a hint?

DA: Well, the reason why it'd be silly to do that, I'm not trying to be secretive or anything, he doesn't wanna it known.

CA: What producers do you admire today?

DA: Sure. I like Scott Walker. Scott Walker is great. And Dre is great. For godsakes, Dre is a great producer. And Diamond D. Diamond D did something, it was so hip, he took a track-- I think it was either from Songs of Innocence or Songs of Experience-- then he took a guitar from another track, on the same album. And where he put the guitar, it sounded so good. If they're creative, if they have the imagination, they can do anything, and it comes out right. {DJ} Shadow's the same way. Shadow's a great guy, Josh is a great friend. His wife is my manager.

CA: Do you think Dre and Shadow saw you as an obscurity and that's why they pulled you out?

DA: No, not at all. Josh has been mentioning me in interviews since '96. I think I met him in the year 2000. Might've been back in 1999, now that I think about it...It was, yeah. We had a mutual friend who is a great friend of his and became a great friend of mine, so this guy brought {Shadow} over.

CA: Are there any artists way back that you wanted to work with but never had the chance to?

DA: Well of course. I would've liked to have worked with Ray Charles. I would've liked to have worked with Aretha Franklin.

CA: What about disco?

DA: I didn't think a lot of it. Well, I liked KC and the Sunshine Band, they were good.

CA: There's a lot of unreleased stuff of yours during the 80's.

DA: Yeah, I made three albums and none of them have come out. I didn't get paid. They're great. They're with fly-by-night people and I have a bad habit of trusting people, and that trust turns to dust. It was all different, I keep getting different all the time. Like the next album's a lot different than the last one.

CA: On the last one, you took old Electric Prunes tracks-

DA: Well the Electric Prunes is a strange thing because those were studio musicians. {On the next one I'm} always going forward, always. {Youth} is what I'm dealing with anyway. They have a lot of albums. I went to London in 2001 to do a promotion thing, and that was an interview every half hour. Then we went to Paris, that was great, and again, an interview every half hour. Then back to London, then to Hamburg, Germany. We did sixteen interviews in eighteen hours in Hamburg, and music critics, journalists, whatever you wanna call 'em, flew in from all over Germany. Reason why we went to Hamburg is that's because it's the media center of Germany, all the headquarters are there.

CA: So how does your royalties work now? If Dre uses a sample of yours on his song, and it gets played on the radio, how's it work?

DA: Oh man, listen, it's been great. Dre's album sold eight, nine million copies or something like that, and you think I'm gonna complain? On that, I got fifty percent because he used all my music-- he just looped it...Knock on wood, it was very nice. I love Dre. I'm in love with Dre.

CA: You see him often?

DA: Nope. Now that I think of it, I've never even spoken to him.

CA: Don't you find that odd?

DA: Nope, nothing in this business is odd, because the business itself is odd. Just to be in it you gotta be weird. I have been {in the business} for years. I've been getting royalties since the 70's. {People wanting to work with me} picked up in 1999.

CA: You strike me as one of the few producers who didn't exploit music maybe in the way some did. Didn't fuck around with the blues to make a buck, in other words.

DA: I don't fuck around with music at all. It's too good. It's my life why would I wanna fuck with it? I've never thought about hit records. Ever. Because hit records depend on a lot of other things. I've always tried to make the best record that I can, and that's what any producer can do. The rest, interplays with how much promotion they're gonna do, how much merchandising-- that's up to the label. Sometimes freak things happen. When "Mercy Mercy Mercy" broke out, Cannon {Adderely} and I were probably the most stunned people around, and Joe Zawinul who wrote it. I mean, Capitol couldn't figure it out. All of a sudden all these orders were coming in and they weren't ready for it, so they had to farm out the pressing for the first three weeks to RCA's plant. They had a big plant and they weren't doing that good. So they were pressing Mercy Mercy for Capitol until Capitol could gear up their own record plants for Mercy Mercy.

CA: How come with Songs of Experience there was poor distribution?

DA: There wasn't...It just seemed that...They can't categorize me and that's difficult for some in the industry, which to me is ridiculous. They should just throw out categories. I'm using Duke Ellington now. Duke hated- So did Benny Carter. Benny hated whenever someone called him like "the greatest living jazz musician". He'd go, "Why does it have to be jazz? You ever watch Ironsides? I wrote the music to that {laughing}." Benny was beautiful, I loved him. Duke said in the thirties or something, "There's only to kinds of music: good and bad." And he's right.

CA: If ain't got that swing it don't mean a thing.

DA: I think he wrote a song called that. {Begins singing it} Doo-wop/doo-wop/doo-wop/doo-wop...Songs of Innocence came first and it was getting some terrific radio play, but they were having a problem because the rock stations weren't sure what the hell it was. A guy who was very hip was Russ Solomon, the guy who owns Tower Records. When that came out he had three stores. One in Sacramento, one in San Fransisco, and one, supposedly the biggest in America, on Sunset. And he personally told them to give me two bins. He always liked my music. So I had a bin in jazz and a bin in rock...The perfect store for me would be everyone was listed by name-- A through Z-- whether they were composers, performers, or whatever. That would be the perfect store. Forget about having these rock sections or classical or jazz. Get rid of the categories, for godsakes.

CA: As an L.A. native, what do you think of the New York City scene during the sixties?

DA: What did I think of it? I thought it was cool. New York's always been cool. Hell, it was cool in the 50's when I first went there.

CA: You had a pretty tough upbringing, self-taught to get into music.

DA: But so did Zappa, Duke Ellington, Benny Carter. So did Wagner. You study. They have books. Frank was a dear friend and we used to compare notes on how we studied. A great deal of it was done in a public library. That's what Bernard Herrmann used to say. Look at his music, god, that score for Taxi Driver is just amazing. Everything he did was great. But there's something about that Taxi Driver score that's so great. He was self-taught. That's not true {that all were self-taught}. A good friend is Randy Newman. I've always told him that I envy his education, and he agrees. It's a lot easier when you have that knowledge. Duke kinda envied Gershwin. He'd say, "George has the knowledge. When I do an extended piece my transitions are kinda weak, they're more like juxtapositions."

CA: I know there was the Easy Rider film stuff with the Electric Prunes, but how come you didn't do more film scores?

DA: I never wanted to.

CA: No? I thought it would be perfect.

DA: I know. Looking back, it was a mistake.

CA: Did people approach you? Directors?

DA: Yes they did. After Songs of Innocence came out, I got three calls. One of them was from George Lucas who was putting his first film, Thk 1138, and I don't know what happen. We talked for awhile and that was that. But Robert Altman was terrific. At that time he was doing his first feature, A Cold Day In The Park, with Sandy Dennis. And the problem was the producers were new, and they were afraid because I had never done a movie. But he was so wonderful, I had so much fun with him. I mean, the guy's about six feet seven. So we have the screening and I see it...And I had seen films before when the color's all wishy-washy, but you get used to that. So we came out and went to this bar, and boy can this guy drink, because I can drink. But he could really drink, Jesus. He's drinking triple scotches {laughing}. I'm drinking double. But we talked about the movie and I said, you know, I don't think we can boil it in fourteen pieces, because anything bigger is gonna wipe out the movie, it's a small movie. But he was the only one out of the three or four people I talked to at that time who actually called me. Because one, I fucked up. There was another science-fiction movie being made by Douglas Strumboli, who's become now the great special effects dude. The producer was Michael Gruskoff, who became very big at 20th Century Fox because he brought in Mel Brooks. The thing is, I had a hangover, it was nine in the morning, I don't think I even got home until 4. I should never make interviews for nine in the morning. So he looked at me and went, "Can you tell me what pictures you've done?" And I just stared at him for a minute and said, "The Good Earth". {Laughing} And that was it, interview over. I don't know why I do these things. I still do them.

CA: But films could still use your stuff.

DA: Well, I've been in them. We started putting all these records into movies, which was Dennis Hopper's idea in Easy Rider. That's where Scorsese got the idea to use all records in Mean Streets-- there's no score. But Easy Rider is the first one to do that.

CA: As of 1970 you were pretty big with the entertainment business-

DA: I was big all over the world, still am. I was probably bigger now than I was then. It's because the world's more open. I mean, I got a royalty statement and there's China and Russia. I should've taken Terri and gone to Russia. Because Russia does not send money out, they freeze it, a lot of countries do that because they can't afford to let the money go, so you gotta go there and spend it. We should've gone, I sold a lot of records there. We had stash of rubles, only problem is, a pack of cigarettes cost a million rubles.

CA: Are you in touch with any of the old producers anymore? Andrew Oldham, Spector?

DA: Nope. Not anymore. The only producer that was a great friend and is a great friend is Jimmy Bowen. He was a great producer, Jimmy had a lot of hits.

CA: What about Quincy Jones?

DA: Oh yeah, Quincy. I forgot about Quincy. {We bring up Nina Rota} He can write that music on the silly side, like on 8 and a Half. But then he can do something like a satyricon, where he uses his entire symphony orchestra, or for The Godfather. I could never figure out how Carmen Coppola won an award for the second when all the cues came out of the first. But Howard Shore won for Lord of the Rings last year and there's a good chance of him winning again this year, and that's fine by me, because he can really write. Do you see The Score with Marlon Brando and Robert DeNiro?

CA: Yeah, I did.

DA: Did you hear the score? Jesus, how could you not?

CA: A terrible film.

DA: The bass player- So what? Listen to the fucking music. I'm not sure if I've watched it all, because I get so hung up on his score. He's got a bass player, reminds me so much of a young Ray Brown. So I listen to the music and don't watch the movie, it's like a concert.

CA: Tell me some classical things you're listening to.

DA: I'm back to listening to Berlioz, who never goes out of style. Symphonie Fantastique, nothing compares. The man was crazy, I love him. Definitely insane. Him and a lot of Moussorgsky. He knew what he was doing.

CA: I always thought Moussorgsky's "Night On Bald Mountain" was a lot like heavy-metal in a lot of ways.

DA: I never thought of it that way. I have it, I listen to it, I have the score to it. And when I listen to it I will think about that. See, you put something on my mind. Incidentally, I love heavy-metal. There's no reason why you can't have jazz play heavy-metal on guitar. Depends on the player. I can't remember it, but in the first Woodstock there was a guitar player who was so fucking great.

CA: I take it you've talked about your work with the Electric Prunes enough.

DA: God, what is there left to say? What's left to say? Is anyone still interested? I'm not, either. It's been printed so many times.

CA: What did you think of Lou Rawls' albums without your production?

DA: Lou could sing for me any day. I don't think he gets the credit he deserves. I will say between '66 and 1970, we outsold Marvin Gaye. And yet you never see Lou, no one talks about him from that era, it's everybody else. I don't understand it, he was the biggest seller in the period, regardless of the category. We'd go number one in r & b and skip top ten on the big chart. He was great to work with. I would say, "Here's the songs, get me the keys." And he would. He'd come in and sing. We got so many Grammy nominations it was absurd.

CA: How about producing Clara Ward?

DA: Oh, Clara Ward. Yeah, that was really weird. That was a very strange album, to say the least {chuckling}. I didn't wanna record her, I was forced to {by the company}. I could've said no by that time, but the way they put it to me, he said he liked me. He said, "I really want you to record her." And if the boss signs her, then you record her.

CA: So in your contract how many albums did you have to do?

DA: No. You're just signed. There's no obligation. What you are is you're given a certain sum of money-- you're either in the black or the red?

CA: You hung out with the Beats a bit. Wally Berman?

DA: Out in Venice. Wally Berman was never a Beat, I was a good friend of his. A woman by the name of Christine McKenna is writing a biography of him right now. I got a call from her and we were on for about three hours, and after awhile I said, "Well how did you know to call me?" She said his son. When I knew Wally he never had a son. She said he had all his records and when he was a kid Wally would tell him about all the stuff we used to do. But Wally was never a Beat, he was a very schooled painter. That was the difference between the New York scene and here. The only guy I knew {there} was Ginsberg, and I had some long conversations with Allen. I get this call from Capitol and it's Allen Ginsberg. The reasons was he was seriously into William Blake, and I was too, ever since I was in my teens-- that's why I did the album. But it shows you what that decade was like. What would happen today if I went into a label and said I have an idea for an album-- I wanna do William Blake. They'd throw me out, of course. What if Alan Parsons went into a label and said I wanna do an album on Edgar Allan Poe. "Edgar Allan Poe? Are you nuts?"

CA: So to be a good producer then, what do you advise?

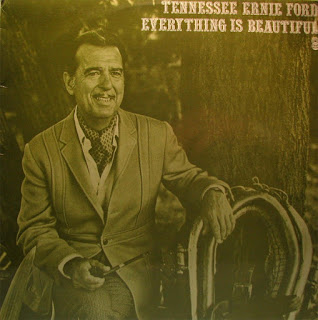

DA: The same thing that always went down. The greatest producer I know was {Chalrie} Lee Gillett. This guy produced Nat {King} Cole and they were like brothers. Like Cannonball and me. But Lee had Nat Cole, Stan Kenton, Tennessee Ernie Ford, and you know? How he found all these songs is amazing. Because at that time, see, there were song-pluggers that worked for the big publishers and the independent publishers as well. And that's how your day was spent: listening to material. For me to find one song for Lou {Rawls}, I'd listen to maybe 80 to find one song before I went, "Yeah, yeah, this is good." And we're looking for ten songs, don't forget.

CA: So on Heavy Axe Carly Simon's "You're So Vain".

DA: That's Cannonball. He produced that album, that's his album {laughing}. We did an album called Accent On Africa, it wasn't exactly the way he wanted it. So after the first take I walked over and said what do you think? He goes, "Don't ask me, this is your album." So Heavy Axe. He has a great memory, doesn't forget, and I don't either, so he called me on the talk-back, "C'mon in here, David, c'mon and here this." I go, "Don't ask me, this is your album." I didn't argue one tune with him. I hated that Steve Wonder tune {"Don't You Worry 'bout a Thing"} I just go okay, fine. Fine. He couldn't figure it out, though, why I was so complient, because he and I could argue a lot. If you look on the back, it's the only one that doesn't say "Produced by David Axelrod and Julian 'Cannonball' Adderley". He was the producer. I do like "My Family".

CA: "Loved Boy" on Mo'Wax was dedicated to your son.

DA: That was dedicated to my son who died. 1970. Died of an overdose. I don't wanna talk about that...Lou sang the hell of it, because he knew my son. As a matter of fact, he was with me when I got the phone call. We were in Alabama, a lot of people were going down there, and...that was that.

CA: You were destitute for awhile during-

DA: Yeah. We were in bad shape. That's not the royal "we", that's Terri and me. We were living in a big room behind this house, and the bathroom had the toilet and the sink had only cold water. Only a hot-plate. Nothing was happening.

CA: But composing.

DA: Certainly. Always.

{Our conversation had been going for over an hour at this point, and shifted to talk a few minutes more about a local record shop nearby. His flu seemed to swelter everything and promised to return back to bed, way behind on his concert which hadn't worked on for a few days. I told him I'd be playing his records and there was a chuckle as if we'd be speaking sometime again.}

--Carson Arnold - March 10th, 2004

DISCOGRAPHY:

LP's:

1957

| |

1958

1959

1960

|

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

The Passion and the Fury of David Axelrod

interview by Linda Rapka

A golden producer in the heyday of Capitol Records, David Axelrod lent his magic to hit jazz, funk and soul records of the 1960s and ’70s. He churned out a succession of gold records and top singles with artists including Lou Rawls, Cannonball Adderley and the Electric Prunes, and his signature sound is a sampling favorite of today’s hip hop artists. His keen eye for spotting unlikely successes garnered him a lasting imprint on some of the most eccentric albums of the era. Sailor-mouthed and charmingly surly, Axelrod minces no words about his improbable highs and cavernous lows during six decades in the industry.

Raised in the tough black neighborhood of South Central, Axelrod started going out to the clubs at 15. “If you were in diapers and you had cash, they would serve you,” he recalled. “We went there because we could get served. But then I started listening to the music.”

Big Joe Turner, Jimmy Witherspoon, Amos Milburn and other prominent black jazz and R&B artists of the Central Avenue scene turned Axelrod on to the world of music. In the late 1950s he spent a stint on the east coast, where he befriended the likes of Charles Mingus, Buddy Collette, Ernie Andrews and Gerald Wiggins. But his love of L.A. soon led him back home, where he found session work drumming for TV and film scores. His shift to producing made waves in jazz circles with his work on hard-bop tenor saxophonist Harold Land’s “The Fox” in 1959.

Known for big beats and deep bass lines, the Axelrod sound was much heavier than typical of that era. “I liked mixing the rhythms like rock with jazz and add classical sounding strings,” he said. “Nobody was doing that. I don’t know why. It seemed like a natural thing to do, I thought.”

He landed at Capitol in 1964 under Alan Livingston, for one simple reason: “That’s where I wanted to be.” Located in Los Angeles, it was the only major outside of New York and Chicago, and he wasn’t about to leave his hometown again. That same year Capitol struck gold with the Beatles, which afforded unorthodox thinkers like Axelrod more leeway to experiment. He did A&R, wrote and produced a succession of gold albums and hit singles including Lou Rawls’ “Dead End Street” and Cannonball Adderley’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy!” and helped steer the company in new directions. His unprecedented move to hire black promoters to push Capitol’s black artists paid off big. His idea to sign blond, blue-eyed pin-up actor David McCallum of “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” fame, despite the fact he had no previous experience and couldn’t sing, landed four hit records. Axelrod was the golden boy.

In 1968 he broke ground blending psychedelic rock with string arrangements on the Electric Prunes’ concept album “Mass in F Minor,” wholly composed, arranged and conducted by Axelrod. Sung in Latin, the album was received as innovative and adventurous and gained heightened popularity when the song “Kyrie Eleison” appeared in the cult film “Easy Rider.”

But the album’s success came back to bite him; it was recorded not for Capitol, but for Reprise. “Livingston had a fit!” Axelrod mused. “After he yelled at me for a while, he said, ‘You’ve got to write an album for us. That’s an order.’ I said, ‘Oh, well OK.’ Like I wasn’t happy about it.”

That year he set to work on his first solo effort. Inspired by the poems and illustrations of English artist William Blake, the end result was a quixotic blend of pop, rock, jazz, theater music, and R&B using a rock orchestra. “Song of Innocence” surprised everyone when it met with widespread critical and popular success. “It turned everything upside-down,” Axelrod said. “Suddenly everyone’s trying to do it. Especially in the U.K.” Another Blake-inspired album, “Songs of Experience,” followed in 1969.

During this time he continued to work with Adderley, Rawls and others including South African singer Letta Mbulu and bandleader David Rose. In 1970, with the exit of Livingston, Axelrod left Capitol. On the verge of making an album putting music to Alan Ginsberg’s celebrated poem “Howl!” tragedy struck when Axelrod’s 17-year-old son died. “Ginsberg was so hip. We talked about it,” he said. “He told me certain things that were gonna happen because of my son dying. And he was right. They did.” A few short years later, close friend and collaborator Cannonball Adderley died of a stroke. Axelrod’s work slowed, and three solo albums he recorded in the 1980s went unreleased.

In the early 1990s his music found renewed interest by the hip hop generation. His beats are sampled all over tracks by Dr. Dre, the Wu Tang Clan, Lauryn Hill, DJ Shadow, De La Soul, Sublime, Lil’ Wayne and others. This surprised no one more than Axelrod himself. “I’m reading that I’m one of the most sampled artists, and I’m going, ‘Where the hell is the money?’” Though everyone was using his music, almost no one was paying royalties. He and his attorney are hoping to stave off drawn-out lawsuits by settling out of court.

In 1993 he released his first album in over a decade, “Requiem: Holocaust,” and several compilations of his earlier work were also released. In 2001 he released the self-titled album “David Axelrod” on British DJ James LaVelle’s label Mo’Wax, which features new arrangements of 30-year-old rhythm tracks originally recorded for an unrealized third Electric Prunes album. For the first time in his career, in 2004 he headlined a sold-out concert at London’s Royal Festival Hall.

Axelrod continues to write music for an hour or two each day, but not for any particular project. “It doesn’t need to be anything that’s gonna be concrete or done,” he said. “It’s just writing. It’s just to keep your mind active physically. You’ve got to stay in shape.”

Now 80, Axelrod has no plans to stop making music anytime soon. “What the hell else am I gonna do?”

Originally published in Local 47 Overture, May 2011

1968

1969

1970

LINER NOTES FOR DAVID AXELROD'S ROCK INTERPRETATION OF HANDEL'S MESSIAH

By Richie Unterberger

Of all the producers to make a mark on the world of jazz and rock in the 1960s and 1970s, David Axelrod had one of the most unusual career paths. Gaining his first notable credits on late-1950s jazz albums, by the mid-1960s he'd combined jazz, soul, and pop as the producer of hit recordings by Lou Rawls and Cannonball Adderley. Given the freedom to create records under his own name, Axelrod was behind some of the most ambitious concept albums of the late 1960s and early 1970s, marrying psychedelic rock, orchestrated arrangements, soul, and funk in adaptations of classic literary, religious, and musical works. One of the most audacious of these was issued on RCA in late 1971 as David Axelrod's Rock Interpretation of Handel's Messiah, referred to from this point onward as Messiah for short.

Rock albums with religious themes were somewhat in vogue around this time. Jesus Christ Superstar reached #1 earlier in the year, and Godspell would go gold not long after that, entering the Top Forty in 1972. Axelrod, however, was not jumping on a bandwagon, and indeed was a pioneer of the approach, his first efforts along those lines dating back about four years before Messiah's release. He arranged and wrote the material on the Electric Prunes' third album, Mass in F Minor (released at the end of 1967), which combined psychedelic rock music and religious themes with classically-oriented horns and strings on tracks sung entirely in Latin. With a different lineup of Electric Prunes, he also composed and arranged their 1968 album Release of an Oath, based on the Kol Nidre, the sacred Jewish prayer recited on the eye of Yom Kippur. By that time, it could be argued that the band's LPs were more Axelrod records than Electric Prunes ones, though their association with David ended after Release of an Oath.

By that time, however, Axelrod was releasing albums in a similar mold under his own name. In 1968, his Song of Innocence took its inspiration from poems by William Blake. So, naturally enough, did its 1969 follow-up, Songs of Experience. These weren't whimsical attempts by Axelrod or Capitol Records to exploit mysticism in the hippie culture, but an expression of an interest that he'd harbored for quite a few years. "If I went to somebody today and told them I wanted to do an album of tone poems to William Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience, they'd throw me out," he told MOJO in 2001. "First question – how much? In the '60s those questions weren't asked. I'd got involved with Blake in my early twenties, reading the poems over and over. I composed the album in a week."

Axelrod's final album for Capitol, 1970's environmentally-themed Earth Rot, used (according to a review in Circus) words "from The Old Testament (particularly Genesis and Isaiah) and from a Navajo legend-poem, 'Song of the Earth Spirit.'" Interestingly, the review also opined that "some of it sounds like Handel's Messiah or a Bach fugue." Axelrod would take on Handel's Messiah for real on his next album, moving to another major label, RCA.

"Sometime in the 1960s I got a nice letter sent to me at Capitol from a young guy named Ron Budnik," explained Axelrod in an interview with Richard Morton Jack. "He wanted a career in the music industry, and wondered if I could give him some advice. I had my secretary schedule an appointment, and we talked. He was knocked out, because no one else he'd written to had replied. By 1971 Ron was working at RCA, and contacted me to ask whether I would be interested in recording the Messiah for them. I said, you bet I would!"

Added Axelrod, "But I knew from the start it was going to be both different and difficult. I worked out arrangements for the sections I wanted to include, and used the usual session players - Carol Kaye on bass, Mike Deasy on guitar, and so on." Budnik was credited as producer, Axelrod taking the writing and arrangement credits. Conducting would be his good friend Cannonball Adderley, who as it happened cut an early fusion album titled Black Messiah around the same time, with Axelrod as producer. Recording engineer Peter Abbott had worked on Axelrod-produced LPs by Adderley and Lou Rawls, as well as rock releases by the Monkees, Fred Neil, and Michael Nesmith.

Axelrod could have hardly chosen a more revered classical work to interpret. Composed by George Frideric Handel as an oratorio in 1741, its text was drawn from the King James Bible and psalms included with the Book of Common Prayer. It had been performed for centuries, and recorded for decades, in countless forms. He likely wasn't worried about offending purists who thought Messiah had no business being modernized, telling Billboard in July 1971, "today you can get away with anything because people are so flexible." By that time, he added, college students had the patience to sit and "dig Mozart and Santana on the changer at the same time." It seemed safe to say that no one else had thought of doing a rock version of Messiah, though as it turned out, another would hit the market around the same time as Axelrod's.

Though some of his earlier recordings had been instrumental, as Messiah is very much a choral work, it made sense that vocals would be prominent in Axelrod's arrangements. Soul-gospel singing, whether choral or solo (as in "Behold a Virgin Shall Conceive," handled by a passionate uncredited woman vocalist, and "Comfort Ye My People," where the duties were given to a likewise uncredited male singer), was very much at the forefront of several tracks. While grand classical-style orchestration was present, there were also plenty of wah-wahing, distorted rock and funk guitar, bass, drums, and organ. There were also plenty of the funky "breakbeats" – the varied but steadily driving rhythms, especially on the drums – that made Axelrod a much beloved source of samples to future generations, kicking in after the first half-minute of the opening track, "And the Angel Said Unto Them." Isolate the brief drum solo about a minute into "Worthy Is the Lamb" for a sample, and few would guess it came from an adaptation of a famous classical work.

Those behind the album made their intentions clear on the LP sleeve. "The text of this work (by Charles Jennings) is the same as used by Handel in 1741 with slight modifications," wrote Axelrod. "Handel's melodies and counterpoint are so beautiful that it was as much fun as work to borrow and alter (or probably to some, mess up) for my interpretation. Hallelujah!" Chipped in Ron Budnik: "On this album is the work of George Frideric Handel, as interpreted by David Axelrod, an artist of this century who shares the same bold, energetic sense of pride as the great composers of the past. Until now an attempt to condense and modify this classic work on a contemporary level has been avoided, probably because of its prominence and singular distinction. It is hoped that Axelrod's work will bring to light and punctuate the creative acumen of Handel in what is considered his finest – the MESSIAH."

Noted Axelrod in his interview with Richard Morton Jack, "I thought it was an interesting piece, but when it was released, I was dismayed to see that they had printed my name far bigger and more prominently than Handel's on the front cover. Oh, god, did I suffer for that! Reviewers had their knives sharpened from the moment they saw it. People forget that once something's recorded, the artist ceases to have an input. I enjoyed the music, though." Phyl Garland was indeed savage when reviewing the album for Ebony: "Handel's bulky corpse must have turned over in its grave when they came up with this one, especially when they got to fooling around with his famous Hallelujah Chorus. The whole thing just seems so unnecessary."

A more straightforward assessment by Martin Bernheimer of The Los Angeles Times found the LP "relatively straight and square, as much concerned with Handel and jazz and the gospel tradition as it is with blatant rock...in several numbers Axelrod uses only a Handelian motive [sic] for extended 'original' elaboration." Stated Axelrod to Bernheimer, "I didn't want any of that bubblegum stuff," adding that it was essentially a matter of "making Handel more accessible."

Coincidentally, another rock adaptation of excerpts from Messiah, with only four duplications, appeared around the same time on a different label, conducted and arranged by Andy Belling. Described by Bernheimer as "essentially loud and funky, from start to finish," the almost simultaneous release of the two albums no doubt hurt the commercial prospects of each one. Owing to the mushrooming popularity of Axelrod's work several decades down the line, however, it is his Messiah that's remembered today, at least when it comes to rock interpretations of Handel's oratorio. – Richie Unterberger

By that time, however, Axelrod was releasing albums in a similar mold under his own name. In 1968, his Song of Innocence took its inspiration from poems by William Blake. So, naturally enough, did its 1969 follow-up, Songs of Experience. These weren't whimsical attempts by Axelrod or Capitol Records to exploit mysticism in the hippie culture, but an expression of an interest that he'd harbored for quite a few years. "If I went to somebody today and told them I wanted to do an album of tone poems to William Blake's Songs of Innocence and Experience, they'd throw me out," he told MOJO in 2001. "First question – how much? In the '60s those questions weren't asked. I'd got involved with Blake in my early twenties, reading the poems over and over. I composed the album in a week."

Axelrod's final album for Capitol, 1970's environmentally-themed Earth Rot, used (according to a review in Circus) words "from The Old Testament (particularly Genesis and Isaiah) and from a Navajo legend-poem, 'Song of the Earth Spirit.'" Interestingly, the review also opined that "some of it sounds like Handel's Messiah or a Bach fugue." Axelrod would take on Handel's Messiah for real on his next album, moving to another major label, RCA.

"Sometime in the 1960s I got a nice letter sent to me at Capitol from a young guy named Ron Budnik," explained Axelrod in an interview with Richard Morton Jack. "He wanted a career in the music industry, and wondered if I could give him some advice. I had my secretary schedule an appointment, and we talked. He was knocked out, because no one else he'd written to had replied. By 1971 Ron was working at RCA, and contacted me to ask whether I would be interested in recording the Messiah for them. I said, you bet I would!"

Added Axelrod, "But I knew from the start it was going to be both different and difficult. I worked out arrangements for the sections I wanted to include, and used the usual session players - Carol Kaye on bass, Mike Deasy on guitar, and so on." Budnik was credited as producer, Axelrod taking the writing and arrangement credits. Conducting would be his good friend Cannonball Adderley, who as it happened cut an early fusion album titled Black Messiah around the same time, with Axelrod as producer. Recording engineer Peter Abbott had worked on Axelrod-produced LPs by Adderley and Lou Rawls, as well as rock releases by the Monkees, Fred Neil, and Michael Nesmith.

Axelrod could have hardly chosen a more revered classical work to interpret. Composed by George Frideric Handel as an oratorio in 1741, its text was drawn from the King James Bible and psalms included with the Book of Common Prayer. It had been performed for centuries, and recorded for decades, in countless forms. He likely wasn't worried about offending purists who thought Messiah had no business being modernized, telling Billboard in July 1971, "today you can get away with anything because people are so flexible." By that time, he added, college students had the patience to sit and "dig Mozart and Santana on the changer at the same time." It seemed safe to say that no one else had thought of doing a rock version of Messiah, though as it turned out, another would hit the market around the same time as Axelrod's.

Though some of his earlier recordings had been instrumental, as Messiah is very much a choral work, it made sense that vocals would be prominent in Axelrod's arrangements. Soul-gospel singing, whether choral or solo (as in "Behold a Virgin Shall Conceive," handled by a passionate uncredited woman vocalist, and "Comfort Ye My People," where the duties were given to a likewise uncredited male singer), was very much at the forefront of several tracks. While grand classical-style orchestration was present, there were also plenty of wah-wahing, distorted rock and funk guitar, bass, drums, and organ. There were also plenty of the funky "breakbeats" – the varied but steadily driving rhythms, especially on the drums – that made Axelrod a much beloved source of samples to future generations, kicking in after the first half-minute of the opening track, "And the Angel Said Unto Them." Isolate the brief drum solo about a minute into "Worthy Is the Lamb" for a sample, and few would guess it came from an adaptation of a famous classical work.

Those behind the album made their intentions clear on the LP sleeve. "The text of this work (by Charles Jennings) is the same as used by Handel in 1741 with slight modifications," wrote Axelrod. "Handel's melodies and counterpoint are so beautiful that it was as much fun as work to borrow and alter (or probably to some, mess up) for my interpretation. Hallelujah!" Chipped in Ron Budnik: "On this album is the work of George Frideric Handel, as interpreted by David Axelrod, an artist of this century who shares the same bold, energetic sense of pride as the great composers of the past. Until now an attempt to condense and modify this classic work on a contemporary level has been avoided, probably because of its prominence and singular distinction. It is hoped that Axelrod's work will bring to light and punctuate the creative acumen of Handel in what is considered his finest – the MESSIAH."

Noted Axelrod in his interview with Richard Morton Jack, "I thought it was an interesting piece, but when it was released, I was dismayed to see that they had printed my name far bigger and more prominently than Handel's on the front cover. Oh, god, did I suffer for that! Reviewers had their knives sharpened from the moment they saw it. People forget that once something's recorded, the artist ceases to have an input. I enjoyed the music, though." Phyl Garland was indeed savage when reviewing the album for Ebony: "Handel's bulky corpse must have turned over in its grave when they came up with this one, especially when they got to fooling around with his famous Hallelujah Chorus. The whole thing just seems so unnecessary."

A more straightforward assessment by Martin Bernheimer of The Los Angeles Times found the LP "relatively straight and square, as much concerned with Handel and jazz and the gospel tradition as it is with blatant rock...in several numbers Axelrod uses only a Handelian motive [sic] for extended 'original' elaboration." Stated Axelrod to Bernheimer, "I didn't want any of that bubblegum stuff," adding that it was essentially a matter of "making Handel more accessible."